It seems that the onset of a new decade is enough to get a lot of folk involved with ed tech questioning its position in the grand scheme of things. There seems to be a whiff of gloom and despondency in the air? I give you the amazing ‘The 100 Worst Ed-Tech Debacles of the Decade‘ piece from Audrey Watters of Hack Education, and Dean Shareski’s ‘I Don’t Think I’m an EdTech Guy Anymore‘ thoughtful reflection as starters for 10.

A lot of us have been assailed by such thoughts before, of course, and no doubt will be again. Our optimism over the undoubted potential of ed tech to improve learner’s life-chances being constantly dashed against the pessimistic rocks of over-enthusiastic IWB rollouts, MOOC hypes and doomed iPad schemes, plus the incessant snipings of traditionalist educators.

A pervasive air of doubt and uncertainty is the perhaps unsurprising outcome of a UK decade of under-investment, Nick Gibb, and cynical erosion of almost every form of educational change by some on social media. As the above articles indicate, things seem just as bad over in the US, again unsurprisingly given that De Vos and Trump are in charge. A distinct whiff of downheartedness and failure seems to be drifting through the new year air….

Festival of failure

So now seems a good time to revisit lessons learned at a Failure Festival that I contributed to some years ago (2012, it turns out, doesn’t time fly?). Curated by Gavin Dykes, and staged by Nesta, participants were asked to reveal their greatest professional failure, and the lessons they had learned from it.

Emma Mulqueeny described how trying to broaden the appeal of her exciting Young Rewired State programme managed to anger the original participants. Tom Kenyon outlined his part in the making of the TV series entitled ‘Jamie Oliver’s Dream School‘, a failure which he felt could be summarised as ‘No Jamie, no dream, and no school’. Claudia Barwell of the Suklaa team described an events failure linked to the creation of some bespoke inappropriate underwear, the details of which now escape me but it had the room in convulsions at the time. My own contribution, predictably, focussed on a disastrous attempt to help bring about educational change by the introduction of technology…

It was the analogue era of the early 80s, I was only three years into my second career as education technologist, and, as part of a move to try and improve teaching and learning, I had been coerced into joining the staff of the worst college in London . I can say ‘the worst college in London’ with a degree of confidence confidence because:

a. I was told it by Learning Resources staff at the ILEA when they asked me to work there,

b. I observed it when working there, and

c. eventually, not long after, it became the only FHE college to have been closed down by the DfE for its overall incompetence (though I believe others have followed it since).

As with almost all education establishments, even Dotheboys Hall, it wasn’t all bad. There were some well-run departments, a few excellent lecturers, and other staff working against the odds to try and give the students a positive experience. And some students did do well, and went on to be successful accountants etc, for the college focussed on business qualifications up to degree level.

There was also some of the worst teaching/lecturing I have ever had the misfortune to encounter. The students that went on to success did this despite, rather than because of, much of this instruction. And also thanks to the efforts of that group of staff who went way beyond the call of duty to mitigate some of the damage wrought by their colleagues.

Accounting for poor pedagogy

The worst teaching practice I have ever seen took place in one of the Accountancy Departments – yes, they taught so many accountants they had to have two departments! This one was located in old primary school buildings in an unfashionable part of Wandsworth. Long narrow rooms housed around 40 students at a sitting. One windowless side wall, and a similarly windowless front wall of the classroom housed enormous blackboards. At the start of a the one and half hour session the lecturer would grab chalk (always white), and begin transcribing from written notes onto one of the boards. The only sound was of squeaking chalk, and the rustle of paper as 40 students started copying the text into their notepads. The lecturer worked along the long board, then the front board. If by some chance the lesson wasn’t over, they then picked up a board rubber, went back to the start, erased what was written, and continued transcription until the bell rang. It was appalling.

The worst teaching practice I have ever seen took place in one of the Accountancy Departments – yes, they taught so many accountants they had to have two departments! This one was located in old primary school buildings in an unfashionable part of Wandsworth. Long narrow rooms housed around 40 students at a sitting. One windowless side wall, and a similarly windowless front wall of the classroom housed enormous blackboards. At the start of a the one and half hour session the lecturer would grab chalk (always white), and begin transcribing from written notes onto one of the boards. The only sound was of squeaking chalk, and the rustle of paper as 40 students started copying the text into their notepads. The lecturer worked along the long board, then the front board. If by some chance the lesson wasn’t over, they then picked up a board rubber, went back to the start, erased what was written, and continued transcription until the bell rang. It was appalling.

My opinion of the appalling treatment of the students was confirmed by the response of an HMI, who was supposed to be interviewing me during a college inspection shortly afterwards, following a lesson observation in the same room. I offered him a coffee, which he refused rather abruptly, and we got about five minutes into the interview when I could tell he was in a bad way, and I asked him if he was OK to continue?

‘No’, he said, ‘do you mind if we do have that cup of coffee I just turned down, and reschedule?’ Coffee supplied, he relaxed a little, and realising he was in supportive company, he opened up and told me he was almost in tears, being overcome with anger after seeing the worst teaching he had ever encountered. Knowing where he had just been, I concurred, and we talked about the experience till he overcame his emotions, and he used my office to write probably the most scathing report that an HMI has ever penned. We had our proper interview the following day, without any mention of the previous day’s experience, apart from a warm handshake and ‘… and thank you again’, as he left.

Ed tech fail…

When the HMI report came in, I was summoned up to Accountancy to discuss the learning resources implications of the damning verdict, and its remediation. In an effort stop the over-teaching that I described above, one of the HMI recommendations was to move from 90 minute to 3 hour time-slots. The inspectorate hope being that this would allow more flexible and student-centred learning, with discussion groups, one to one tutorials, seminars etc. I was taken to one of the lecture rooms to discuss the learning resources implications. The lecturer pointed at the other long wall, and said that if the sessions were to be three hours long, he would need new blackboards along the third wall as there would be so much more for the students to transcribe!

Let me reassure you at this point that my ed tech failure was NOT to provide the requested blackboards. No, dear reader, it was far worse than that. This was the era of the overhead projector, a device welcomed by many teachers because it actually allowed them to maintain eye-contact with students as they taught. It had become fashionable elsewhere in the sector to issue students with transparent acetate ‘foils’ and marker pens, and allow them to prepare presentations on topics, for them to share with their peers. My radical solution was therefore to remove the tyranny of blackboard transcription by equipping the rooms with OHPs, that the students could use to lead tutorial sessions and seminars, using material they had prepared in the adjacent library. The new Head of Dept, the Librarian and I were delighted to come up with such a transformative solution.

Let me reassure you at this point that my ed tech failure was NOT to provide the requested blackboards. No, dear reader, it was far worse than that. This was the era of the overhead projector, a device welcomed by many teachers because it actually allowed them to maintain eye-contact with students as they taught. It had become fashionable elsewhere in the sector to issue students with transparent acetate ‘foils’ and marker pens, and allow them to prepare presentations on topics, for them to share with their peers. My radical solution was therefore to remove the tyranny of blackboard transcription by equipping the rooms with OHPs, that the students could use to lead tutorial sessions and seminars, using material they had prepared in the adjacent library. The new Head of Dept, the Librarian and I were delighted to come up with such a transformative solution.

In my enthusiasm I had forgotten two key facts. One was that the Head of Dept, despite his enthusiasm, was unprepared to challenge head-on the poor pedagogy he observed daily, and wouldn’t provide any professional development time to shift the lecturers’ approach. The second key fact that I forgot was that the OHPs of the day came came with twin rollers, and rolls of transparent acetate.

You are probably ahead of me here already? When I next visited the Accountancy dept, to see how they were getting on with their new OHPs, one of the lecturers stopped me in the corridor, and thanked me profusely for transforming his teaching. He then proudly showed me the roll of acetate onto which he had transcribed his notes, and described how he could now just sit at the front and slowly wind through the roll while the students copied them down! He even added insult to injury by saying his wife was also delighted, as his laundry was now so much easier when his clothes were not covered in chalk!

Like I said at the start, pedagogy will beat technology, every time! Even bad pedagogy.

The happy ending

In some ways, this experience represented a nadir in my ed tech journey. But not all was lost. At around the same time, in another part of the same college, I became intrigued by the sessions on spreadsheets that different accountants were being taught, on a suite of Apple II computers. I acquired some different computers for staff to come to my workshops on the various sites, and prepare their learning resources. Shortly after, I left the college to go and work at the local authority’s new Educational Computing centre, to help them produce more teacher-friendly resources. Which took me off on a whole new digital career. So I do have that to thank the college for.

Thus I do have some positives to take away, along with my biggest personal ed tech failure, which helps soften the blow. As indeed did the closure of the college shortly after, when it was deemed to be beyond all hope. And for those who like really happy endings, the good sections of the college were adopted by other, far better local FE and HE establishments, so their educational impact was actually improved.

On into 2020

In the midst of the current uncertainty, there are sadly those who still feel the way forward with ed tech is hype, rather than realism. Today, as I prepared this piece, the BBC published one of those silly headlines that makes every sensible person in ed tech groan with despair – “Language apps: Can phones replace classrooms?“. Sometimes it’s still as if the old BS about ‘tech replacing teachers’ hasn’t ever gone away?

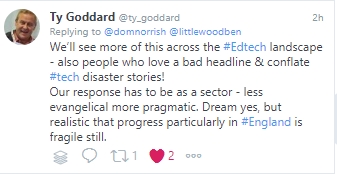

Ty Goddard tweeted an appropriate response, which offers excellent advice for all those of us still keeping the faith the the potential of ed tech to keep in mind.

As the New Year dawns, and BETT 2020 approaches, we are undoubtedly in for more such stories, and the annual twitter spats between the ed tech hypers, and the ed tech naysayers. Let’s learn from that Nesta Failure Festival, and reflect that those who eventually succeed have often failed previously… sometimes have failed repeatedly.

Hype, and inappropriate pedagogy, have undoubtedly contributed to past ed tech failures, sometimes on a massive scale. And as Ty points out, there are always those with an eye for a bad headline and keen to conflate bad ed tech stories. But I am sure that enough of us have seen a combination of good technology and pedagogy make a real difference to the lives of learners to keep the faith, even at times such as these?

So hopefully I will again see you all at BETT 2020! It may be full of hype, but as one who has attended BETT almost every year since 1985, and often written about it (e.g. 2015, 2016, 2017) it is also the place you will meet some of the nicest educators on the planet, and get the chance to bring a pragmatic, realists eye to bear on the next generation of education technology.

Post Script

P.S. When I described the above epic ed tech fail at the Nesta event, a Guardian journalist wrote this up next day, saying mine was an ‘apocryphal account’. Let me assure you, as I did her via the Guardian Comments section, this story was NOT apocryphal (and to be fair, her report was subsequently edited to remove the slur).

The college was called South West London College, based in Tooting, Streatham and Wandsworth. The building I occupied was demolished to build a Sainsbury’s, right next to Tooting Broadway tube station, formerly also famous for the opening credits of Citizen Smith. With a branch of another, far better, college now placed above it!

I use Edtech in my classrooms, and write about it on my site but agree 100% the teacher, their knowledge, enthusiasm and passion is what creates the learning environment, not what ever IPad or VR headset is thrust into a students hands. We have just put Interactive whiteboards into each and every classroom of the school, although the noble aim was to allow students to interact more in the lesson, present topics, learn skills otherwise unknown it hasn’t been achieved.

I wander the halls sometimes, when i have some spare moments, just to see how its being used. As a blackboard, and now and then as a TV is what i see. They had the money to buy the boards, but didn’t think paying or allowing time for the training was a worthwhile use of funds.

Still, chalk costs are a little down now.